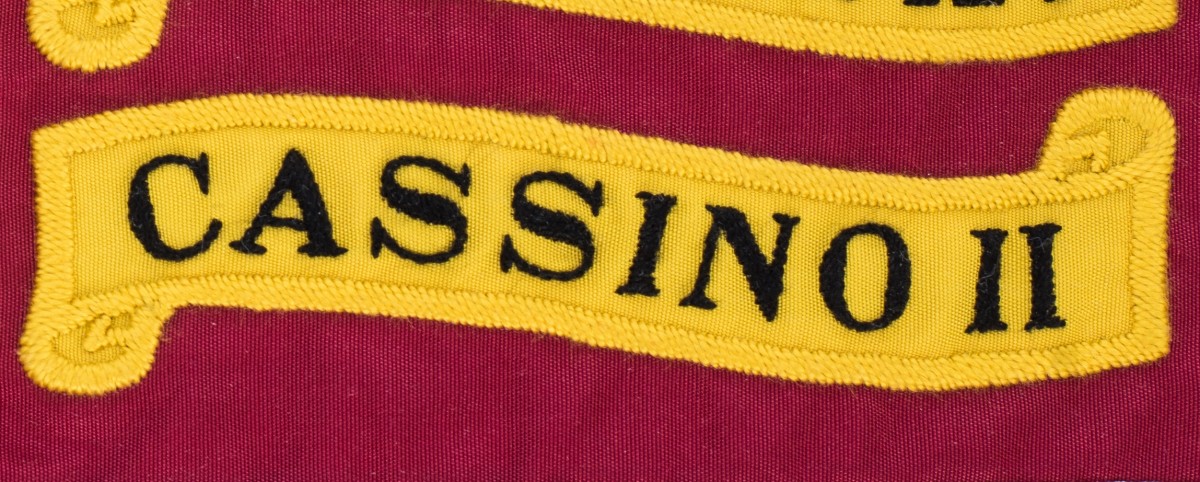

Battle Honour CASSINO II

The Battle Honour CASSINO II is emblazoned on the King's Colour of the Royal Irish Regiment.

The story of our forebears' fighting at Cassino was related in The Blackthorn 2010 edition in an article written by the military historian, author and broadcaster Richard Doherty. The article below is reproduced with his permission.

Monte Cassino

The role of 38 (Irish) Brigade

(Above, Allied bombers strike at Cassino town on 15 March 1944, a month after the bombing of the monastery. The photo was taken from Monte Trocchio, where the briefings for commanders in the final battle were conducted. (US official))

(Above, Allied bombers strike at Cassino town on 15 March 1944, a month after the bombing of the monastery. The photo was taken from Monte Trocchio, where the briefings for commanders in the final battle were conducted. (US official))

As dawn broke the advancing infantry found themselves in standing corn with enemy machine-gun positions only seventy yards away. Fortunately, the corn provided some concealment. Then enemy tanks appeared on the scene. What followed was almost farcical. On this late spring morning, a thick blanket of fog lay over the valley and the tank crews were all but blind. They milled about in search of the infantry. One platoon commander had a narrow escape from being run over by a tank, but the fog was a blessing to the infantry since the tanks were virtually useless in such conditions.

An exercise gone awry? No, this was Italy 1944, and the final battle for Cassino. The infantry were 6th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the spearhead of 38 (Irish) Brigade’s attack. In turn the Irish Brigade led 78th (The Battleaxe) Division’s breakout from the bridgehead created by 4th (British) and 8th (Indian) Divisions. This was one of the critical points in breaking the deadlock along the Gustav Line against which Allied forces had been stalled since January.

One of the pivotal battles of the Second World War, Monte Cassino epitomises the Italian campaign for most people. With memories of the conflict fading, the name of the mountain, and its Benedictine monastery, is often the only knowledge many people have of the war in Italy. For the diminishing band of survivors, and the families of those who fought there, Monte Cassino manages to encapsulate the campaign: grinding fighting against a determined enemy in a country custom-made for defence and in all weather conditions from snow and freezing rain to the warmth of an Italian spring. [Above right, the Abbey prior to the Second World War. (Image© R Doherty)]

One of the pivotal battles of the Second World War, Monte Cassino epitomises the Italian campaign for most people. With memories of the conflict fading, the name of the mountain, and its Benedictine monastery, is often the only knowledge many people have of the war in Italy. For the diminishing band of survivors, and the families of those who fought there, Monte Cassino manages to encapsulate the campaign: grinding fighting against a determined enemy in a country custom-made for defence and in all weather conditions from snow and freezing rain to the warmth of an Italian spring. [Above right, the Abbey prior to the Second World War. (Image© R Doherty)]

For the Royal Irish family, of course, it is one of the battle honours emblazoned on our Colours. It appears as Cassino II, the strange definition arrived at by the Battle Honours Committee in the 1950s for the events in which 6th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers and 2nd London Irish Rifles, forming 38 (Irish) Brigade in 78th Division, fought. Our antecedent regiments took part in the fourth and final battle of Cassino but the Committee, in its wisdom, chose to divide the Gustav Line fighting into only two battles of Cassino.

But the final battle was not the Irish Brigade’s first encounter with Monte Cassino. Earlier, 78th Division had been transferred to the extemporised New Zealand Corps during the third battle. When that offensive was called off on 23 March, none of 78th Division’s brigades had been called forward to do battle, although the Irish Brigade was deployed along the Rapido river facing the village of Sant’Angelo. Three days later the Division, now returned to XIII Corps, occupied a sector from Cassino’s railway station to Monte Cairo in the heights overlooking the abbey. There followed almost a month of very dangerous and difficult soldiering in what one veteran described as ‘sangar life’. In their mountaintop positions companies could be resupplied only under cover of darkness and by mule. Many mules died with their handlers as the nightly maintenance convoys made their way up narrow tracks that were registered by the German artillery, mortars and machine guns.

Nor was it safe to leave the cover of the sangar in daylight. Any movement attracted machine-gun or mortar fire. Brigade HQ, in Caira village, was reputedly the most shelled and mortared spot in Italy. (Brigadier Pat Scott, recovering from a broken ankle and unable to move quickly or far, commented that his HQ was ‘a good place to be away from’.) But, when darkness descended, the Irish Brigade ruled the ground between the two sides. The French, from whom the Brigade had taken over, had not patrolled at night allowing the Germans to dominate the darkness. However, Bala Bredin, commanding 6th Inniskillings, was determined that his men would dominate the ground. Aggressive patrolling soon ensured that this happened.

It was at Caira village on 6 April that the legendary Father Dan Kelleher [left], the Brigade’s RC chaplain, earned the MC for rescuing wounded Faughs under heavy fire. Brian Clark, then Adjutant of 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, later commented that had Father Dan been serving with an English brigade he would have been put up for the VC ‘but Irish soldiers thought that [what he did] was routine for a padre’.

It was at Caira village on 6 April that the legendary Father Dan Kelleher [left], the Brigade’s RC chaplain, earned the MC for rescuing wounded Faughs under heavy fire. Brian Clark, then Adjutant of 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, later commented that had Father Dan been serving with an English brigade he would have been put up for the VC ‘but Irish soldiers thought that [what he did] was routine for a padre’.

Finally, 38 (Irish) Brigade handed over their positions to the Poles from whence the latter would launch their assaults on the Abbey and Point 593 in the early hours of 12 May. Brian Clark recalled that the Poles’ adjutant could speak no English, that he (Clark) could speak no Polish, and that the handover was conducted in the one language they had in common – German.

So let’s rejoin 6th Inniskillings as they probed forward on the morning of 15 May. As the fog lifted a squadron of Shermans of 16th/5th Lancers crossed the Piopetto river [right, foreground] to support the Skins. Within thirty minutes, Massa Tamburrini had fallen and Bredin’s men were ready to move to their next reporting line, Grafton. Shortly after noon, they reported all objectives taken; battalion losses were light, but the Germans had paid a heavy price. The next phase of the operation involved 2nd London Irish Rifles taking up the baton from the Inniskillings. But, as the CO of the Rifles, Ian Goff, and the CO of 16th/5th Lancers, John Loveday, held their final O Group, German shells, aimed at the Inniskillings, crashed down nearby. Both COs were injured fatally.

So let’s rejoin 6th Inniskillings as they probed forward on the morning of 15 May. As the fog lifted a squadron of Shermans of 16th/5th Lancers crossed the Piopetto river [right, foreground] to support the Skins. Within thirty minutes, Massa Tamburrini had fallen and Bredin’s men were ready to move to their next reporting line, Grafton. Shortly after noon, they reported all objectives taken; battalion losses were light, but the Germans had paid a heavy price. The next phase of the operation involved 2nd London Irish Rifles taking up the baton from the Inniskillings. But, as the CO of the Rifles, Ian Goff, and the CO of 16th/5th Lancers, John Loveday, held their final O Group, German shells, aimed at the Inniskillings, crashed down nearby. Both COs were injured fatally.

Major John Horsfall, second-in-command of the Rifles, took over the battalion and Pat Scott joined him while Bala Bredin made his way back to brief him on what lay ahead. The second phase of the attack was postponed until the following morning, to allow 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers to move into position for their part in that phase. Thus it was that 2nd London Irish put in their attack the following morning, with H Hour at 9 o’clock. The battalion advanced three companies up (all infantry battalions had four rifle companies at this time) with H Company, commanded by Major Desmond Woods MC, in the centre, E on the left and G on the right. H Company’s objective was Casa Sinagoga, a cluster of farm buildings.

Pat Scott had laid on a heavy supporting artillery programme with the seventy-two 25-pounders of the divisional artillery reinforced by medium guns from the corps artillery. The guns opened up on time and John Horsfall described them as being ‘so perfectly timed that the reports of individual guns were lost in the avalanche of projectiles screaming over our positions’. He had warned the attacking troops to ‘lean into’ the bombardment, ignoring the danger from rounds falling short, so as to reduce the possibility of the Germans recovering and manning positions as the shelling crept forward.

Pat Scott had laid on a heavy supporting artillery programme with the seventy-two 25-pounders of the divisional artillery reinforced by medium guns from the corps artillery. The guns opened up on time and John Horsfall described them as being ‘so perfectly timed that the reports of individual guns were lost in the avalanche of projectiles screaming over our positions’. He had warned the attacking troops to ‘lean into’ the bombardment, ignoring the danger from rounds falling short, so as to reduce the possibility of the Germans recovering and manning positions as the shelling crept forward.

[Above, 'O Group at Monte Cassino', by David Rowlands]

Desmond Woods was soon receiving reports from one of his platoons of being hit by ‘shorts’ from British guns. But it was enemy defensive fire being put down on the Rifles’ side of the bombardment, and it was causing casualties. Lieutenant Michael Clark MC, the right platoon commander, was killed while Lieutenant Geoffrey Searles, an American commanding the left platoon, was injured not long afterwards.

Of this shelling Desmond Woods wrote:

I will never forget the noise. … One tried to move from one shell-hole to the next and I remember diving into a shell-hole and a chap – one of the riflemen from my Company HQ – landing on top of me, and I said, ‘get up, we must go on’. There was no movement; he was dead – he had a bit of shrapnel through his neck. … About halfway through the attack … the barrage dwelt for ten minutes and we were able to get down to ground. One wondered would anybody be able to live under this barrage as far as the Germans were concerned, but by God they could.

The troop of Sherman tanks of 16th/5th Lancers supporting H Company also came under fire. As the attackers advanced, the shelling intensified with mortars and machine guns adding their contribution. Major Woods recalled that he was deafened completely by the noise, as well as being ‘completely dazed … and I am sure the remainder of the Company were [as well]’.

As the Rifles closed on Casa Sinagoga the fighting became even more intense. Then the Shermans ran into trouble in the shape of German anti-tank guns which scored several hits and brought the tanks to a halt. Infantry had already penetrated some of the forward enemy positions, but it was vital that the tanks be able to advance to allow the infantry to secure their objective. At that stage Corporal Jimmy Barnes [right] took matters into his own hands.

As the Rifles closed on Casa Sinagoga the fighting became even more intense. Then the Shermans ran into trouble in the shape of German anti-tank guns which scored several hits and brought the tanks to a halt. Infantry had already penetrated some of the forward enemy positions, but it was vital that the tanks be able to advance to allow the infantry to secure their objective. At that stage Corporal Jimmy Barnes [right] took matters into his own hands.

With both his platoon commander and sergeant out of action, Barnes identified the anti-tank gun that was doing most damage – an 88. He led his section forward to attack it but one by one the men were cut down by machine-gun fire on their left flank until Corporal Barnes remained alone. He went on by himself and then he fell dead, cut by a machine gun, but by then the crew of the 88mm had baled out and the tanks were able to get forward once again.

Almost in his dying moments, Jimmy Barnes had lobbed a grenade into the gunpit, killing at least one member of its crew and prompting the others to flee. In the aftermath of battle, Desmond Woods recommended Jimmy Barnes for a posthumous VC, but the recommendation was unsuccessful, and the young Monaghan man did not even receive a Mention in Despatches. This decision grieved Desmond Woods for the rest of his days. He received a Bar to his MC for his leadership that day as H Company, following Jimmy Barnes’ act of self-sacrifice, was able to secure its objective although company strength was down to about a dozen men, all ‘smothered in brick dust, and their eyes the only bright thing about them’.

Major Mervyn Davies’ E Company also secured its objective in Sinagoga wood. Support from the Lancers was critical as E Company took about sixty prisoners from 90th Panzer Grenadier Division. They had also lost both forward platoon commanders and, as they consolidated their positions, came under fire from Nebelwerfern. This ‘stonk’ killed ‘two of the best men in the Company, Sergeant Mayo MM and Corporal O’Reilly MM’.

G Company was also firm on its objectives and 2 LIR had done most of its job, but at a terrible price with twenty dead and eighty wounded. However, they had taken prisoner 120 Germans and captured nine enemy tanks. In the aftermath of battle the Rifles buried more than 100 German soldiers while the battalion medical staff assisted wounded from both sides. In fact, a German MO arrived to assist the Rifles’ MO as did several German stretcher-bearers. With Casa Sinagoga secure and the support weapons and anti-tank guns in position, the survivors of E and H Companies pressed on for another half mile, securing Colle Monache ridge before nightfall. Resistance was light.

It was now the turn of 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers, the Faughs, to continue the advance, to the reporting line Fernie, on 17 May. At midnight on the 16th/17th, the Faughs moved into their concentration area. For them the previous few days had been relatively quiet but that was to end when they began their attack on the morning of the 17th. Once again, a massive artillery programme was laid on in support while a squadron of 16th/5th Lancers provided armoured support. As the Faughs left their start line, so too did the Lothians and Border Horse whose task was to strike out on the Irish Brigade’s left front to and beyond the village of Piumerola.

C and D Companies led the Irish Fusiliers’ advance with Majors Jimmy Clarke MC and Laurie Franklyn-Vaile respectively commanding. A and B Companies were held in reserve to follow through. The opposition had been strengthened by a number of Fallschirmjäger – paratroopers – who were always hardy and determined opponents. As the Faughs moved forward from the start line they came under heavy and accurate fire from mortars, artillery and machine guns. Less than fifteen minutes after stepping off on his advance, Major Laurie Franklyn-Vaile was killed. The death of their popular Australian commander was a blow to C Company, but his men continued their advance on their objective. Also dead was Major Robert Gill, squadron leader of B Squadron 16th/5th Lancers.

C and D Companies led the Irish Fusiliers’ advance with Majors Jimmy Clarke MC and Laurie Franklyn-Vaile respectively commanding. A and B Companies were held in reserve to follow through. The opposition had been strengthened by a number of Fallschirmjäger – paratroopers – who were always hardy and determined opponents. As the Faughs moved forward from the start line they came under heavy and accurate fire from mortars, artillery and machine guns. Less than fifteen minutes after stepping off on his advance, Major Laurie Franklyn-Vaile was killed. The death of their popular Australian commander was a blow to C Company, but his men continued their advance on their objective. Also dead was Major Robert Gill, squadron leader of B Squadron 16th/5th Lancers.

[Right, Maj Gill's headstone in CWGC Cemetery, Cassino. (Image© R Doherty)]

A young officer of the Faughs, Lieutenant Jim Trousdell, recalled his platoon’s part in the attack.

It was still dark as we waited on the start line for the barrage to lift and our advance to begin. The noise was terrific. When we did move forward, I found it difficult to keep up with the barrage due to various interruptions such as keeping in line with the troops on either side of us. The only Germans that I saw were two dead killed by our shellfire on the objective. I recall coming up to a farmhouse and throwing a 36 grenade inside in case it was still occupied but the late inhabitants had left – in a hurry it appeared as a half-eaten breakfast was on the table.

There was a certain amount of enemy shell and mortar fire. The only [C Company] casualties as far as I can remember during this battle were the company commander and his runner, both killed by a shell, both a great loss.

Both C and D Companies took and consolidated their objectives in less than two hours. With supporting arms in place, Captain Brian Clark, the Adjutant, brought Tac HQ forward and, a few hours later, A and B Companies passed through to a battle that lasted all afternoon. During that time the pair of Faugh companies secured the key points overlooking Highway 6, the Via Casilina, the main Naples–Rome road and the escape route for the defenders of Monte Cassino itself. Brian Clark reported the securing of Fernie to the brigade commander at 1500 hours and, immediately, was told to exploit the situation.

Exploitation took the form of D Company moving up to secure a group of buildings close to Highway 6. From this base, when darkness had descended, Lieutenant Jimmy Baker took a patrol forward to disrupt traffic on the road. Calling down mortar fire, Baker caused considerable discomfort to the retreating Germans.

The Faughs’ interdiction of Highway 6 was a clear indication to the German command that it was time to withdraw from Monte Cassino. But there was still work to be done by the Irish Brigade. Although Brigade HQ had been unable to contact the Lothians and Border tanks that had set off for Piumerola, Brigadier Pat Scott was assured by 26 Armoured Brigade HQ, the Lothians’ parent formation, that the Scottish yeomen had advanced beyond Piumerola. Such success had to be consolidated and exploited by infantry and so the Divisional GOC ordered the Irish Brigade to seize the ground overlooking Piumerola, a task Pat Scott gave to the Inniskillings.

And so Bala Bredin’s Skins went forward again but not before a memorable O Group ‘each paragraph of the orders being punctuated by the arrival of a salvo of Nebelwerfer bombs’. The Battalion faced an unclear situation: they didn’t know if there were still Germans in Piumerola; they had been told that the Lothians were thereabouts; they had also been told that the Derbyshire Yeomanry – 6th Armoured Division’s recce unit – were pushing towards Aquino. To clarify the tactical situation, Lieutenant Colonel Bredin and his supporting squadron leader of 16th/5th Lancers went forward to the Faughs’ position at Massa Cerro from where they carried out a reconnaissance. And it was at Massa Cerro that 6th Skins concentrated in readiness for their advance.

And so Bala Bredin’s Skins went forward again but not before a memorable O Group ‘each paragraph of the orders being punctuated by the arrival of a salvo of Nebelwerfer bombs’. The Battalion faced an unclear situation: they didn’t know if there were still Germans in Piumerola; they had been told that the Lothians were thereabouts; they had also been told that the Derbyshire Yeomanry – 6th Armoured Division’s recce unit – were pushing towards Aquino. To clarify the tactical situation, Lieutenant Colonel Bredin and his supporting squadron leader of 16th/5th Lancers went forward to the Faughs’ position at Massa Cerro from where they carried out a reconnaissance. And it was at Massa Cerro that 6th Skins concentrated in readiness for their advance.

[Left, 6th Inniskilling, moving up to 'leapfrog' 2nd London Irish at Cassino, May 1944 (© Crown Copyright)]

From a recce patrol of tanks and infantry sent forward towards Piumerola came the news that the Germans still held the village and that the Lothians were some 600 yards away. With contact re-established with the Scottish tankers, Bredin learned that Piumerola was held in some strength: there were anti-tank guns, self-propelled guns and a Mark IV tank. Having made a further recce from the Lothians’ positions, Bala Bredin laid a plan for A and C Companies and a squadron of tanks to assault Piumerola while the artillery swamped the village and surrounding buildings with heavy fire. D Company was to attack at the same time, their effort directed on Campolorgo; the Lothians ‘were persuaded to support this part of the attack’.

As the Skins formed up on their start line, they came under fire from artillery and mortars, suffering half an hour of this before H Hour, 1745 hours. Casualties included their redoubtable CO. Bala Bredin was hit in both legs but refused medical treatment and advanced with his men, strapped to the bonnet of a jeep. Only when he passed out from loss of blood, was he evacuated from the field. Command was assumed by Major John Kerr MC, who had been the battalion signals warrant officer less than two years before.

So keen were the Skins to escape the purgatory of the start line that there was ‘an almost indecent haste’ in their attack. Within fifteen minutes, and in spite of the problem posed by a sunken road, tanks and infantry were closing on the village while D Company was also advancing inexorably. Prisoners began coming back and the appearance of Fallschirmjäger with their hands in the air ‘was unusual and heartening’. There followed house-to-house fighting but, as night fell, the Inniskillings were consolidating. The usual German counter-attack never materialised as the Fallschirmjäger had been taken completely off balance at what was intended to be a check point in their retreat from Monte Cassino; they had been preparing defensive positions when bounced by the Skins.

The Inniskillings had advanced further than Pat Scott had intended. Unable to stop their full-blooded advance, he chose to reinforce their effort by deploying 2 LIR on their left flank. With the help of 17th Field Regiment – who called themselves the Royal Hibernian Artillery – and 16th/5th Lancers’ tanks, the Rifles had taken their objectives by twilight. That night E Company caught a small Fallschirmjäger patrol in their sector, most of whom fled, although two were captured.

The fall of Piumerola led to the final German order to abandon the Monte Cassino positions. In the darkness of that night, the German paras slipped away and, next morning, a hastily made pennant of 12th Podolski Lancers, proclaimed that the Poles had secured Monte Cassino and the ruins of the famous Benedictine abbey.

The Gustav Line had crumbled after a week of confused and bloody fighting. The Irish Brigade’s critical part in that fighting was acknowledged by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese, Eighth Army’s commander and Major General Charles Keightley, GOC of 78th Division. In passing on Leese’s message, Keightley added his personal endorsement.

As the leading Bde of the Division over the R. Rapido you set the speed of the advance of the Division, and from the high standard you set we never looked back.

Each of your Bns has had its battle, and in each case Bn objectives were gained and passed. This is a fine record and reflects the greatest possible credit on every officer and man who went through the battle.

Pat Scott wrote that

I cannot speak too highly of the magnificent spirit and fighting qualities shown by all of you during the first very difficult days of the advance that brought us here.

More is yet to be done, ROME is the main objective and the Army knows that the Irish Brigade and all the magnificent fighters in its three famous battalions are certain to rise to any occasion.

How true were those words, both in respect of what the Brigade had achieved at Cassino and in what it was still to achieve in the eleven months of fighting that lay ahead. Undeterred by difficulties, Pat Scott’s battalions would continue to clear the way to northern Italy and final victory.

Richard Doherty