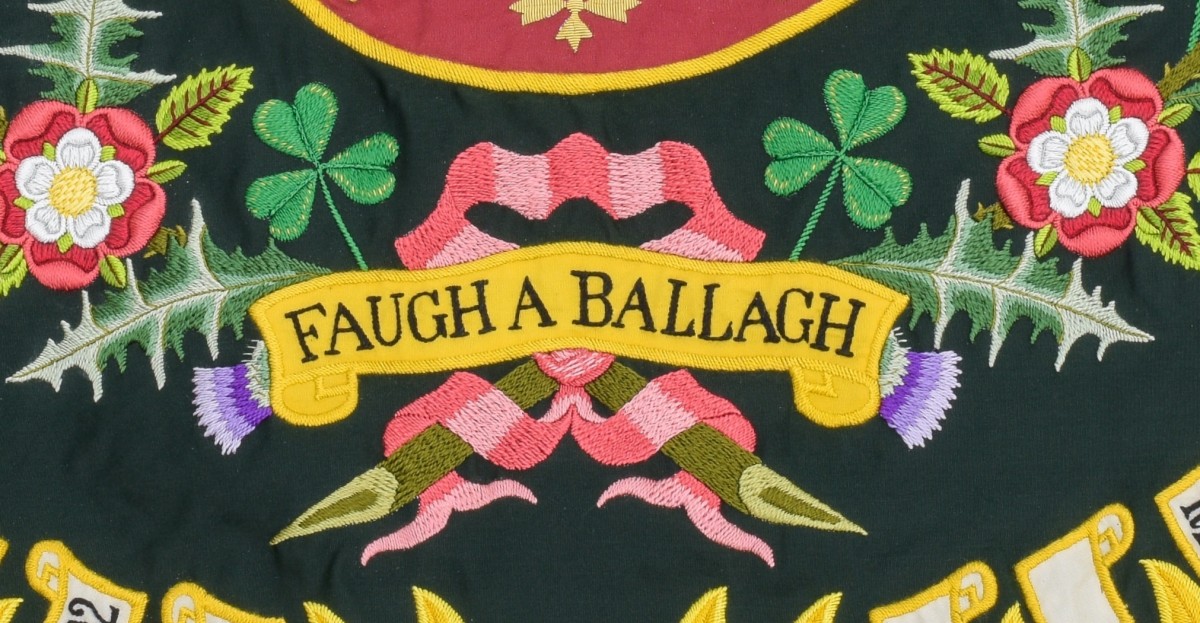

The Origins of 'Faugh a Ballagh' and the Green Hackle

So used are we, in The Royal Irish Regiment, to the sight of the green hackle and to the motto ‘Faugh a Ballagh’ that we often assume that these distinctions have always been with the Regiment and its predecessors. But this is not so, as documents in the National Archives at Kew show. Although the motto was used by the 87th and, after 1881, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), it was not accepted officially by the War Office until 1899.

So used are we, in The Royal Irish Regiment, to the sight of the green hackle and to the motto ‘Faugh a Ballagh’ that we often assume that these distinctions have always been with the Regiment and its predecessors. But this is not so, as documents in the National Archives at Kew show. Although the motto was used by the 87th and, after 1881, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), it was not accepted officially by the War Office until 1899.

On 10 July of that year, Lieutenant General Sir Alexander Cobbe KCB, then Colonel of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), wrote to the Under Secretary of State at the War Office, asking that ‘my Regiment be permitted to wear on its full Head-dress a Green Hackle and to bear on its Colours the motto ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’. Cobbe went on to justify the adoption of the green hackle with an entirely spurious argument: that the 1st Battalion (the 87th) wore a green hackle when it was raised in 1793, a claim supported by a picture in the regimental records; and that the 2nd Battalion (the 89th) had a head-dress dating from 1825 which also bore a green plume or hackle.

In fact, neither antecedent regiment had possessed such a distinction. The green hackle of 1793 and that of 1825 were flank company distinctions; the right, or grenadier, company of a line infantry battalion wore a white hackle while the left, or light, company, wore a green hackle. What General Cobbe’s argument was based on were light company hackles.

Although one would have expected this to have been recognised in the War Office, the argument was accepted and the only obstacle seems to have been that of cost. A calculation was made based on the cost of an individual hackle being 7½d with a ring costing a further ½d and fitting – at 2¾d – bringing the cost per soldier to 10¾d (less than 5p in today’s currency). Since the first cost of providing all soldiers with their hackles was under £44, with an annual recurring cost of less than £9 (based on one in five of 988 personnel requiring hackles each year), the Adjutant General, Sir Evelyn Wood, asked the Commander-in-Chief to approve the proposal.

Such approval was forthcoming and Wood wrote to the Secretary of State to seek affirmation of the ‘provision of green hackle for R. Irish Fusiliers. The cost is nominal.’ Thus was the green hackle granted. And some might say ‘just in time’. In his letter to the War Office, General Cobbe had referred to green as the ‘National Colour’ and expressed the view that it would help recruiting for the Regiment, which was at a very low ebb in its own district. Had the request been made a year later, it is likely that it would have been too late. By then Queen Victoria had approved the raising of an Irish Regiment of Foot Guards, which also applied for permission to wear a green plume in its head-dress. The ‘Micks’ were refused the distinction since it was already held by the Faughs.

The story of the motto is very different. Since Cobbe had asked for permission to carry it on the Colours at the same time as he sought approval for the green hackle, the two requests are included in internal correspondence in the same file. There are notes relating to the approval of the green hackle in which it is commented that ‘we refuse the motto’. One note dated 7 September 1899 – the writer is unknown – wrote ‘I have no doubt that there is sufficient reason for refusing to let them have ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’ on their colours – what is it?’

The story of the motto is very different. Since Cobbe had asked for permission to carry it on the Colours at the same time as he sought approval for the green hackle, the two requests are included in internal correspondence in the same file. There are notes relating to the approval of the green hackle in which it is commented that ‘we refuse the motto’. One note dated 7 September 1899 – the writer is unknown – wrote ‘I have no doubt that there is sufficient reason for refusing to let them have ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’ on their colours – what is it?’

The Adjutant General seems to have been the major obstacle to this request. General Cobbe had justified it thus:

‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’ was the War Cry of the 87th Regiment, Commanded by the late Field Marshal Lord Gough, at the Battle of Barrosa in 1811 when the Eagle (encircled with a wreath of laurel) of the 8th French Regiment was captured, and in my young days we were known as the ‘Old Faughs’ or the ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh Boys’. Not only does the 1st Battalion still retain this soubriquet but the 2nd Battalion (the old 89th Regiment) is proud to be known by the same name.' Interestingly, someone has written in the margin of this paragraph ‘& 88th’, suggesting that the Connaught Rangers also used the motto. This would not be surprising since both were Gaelic-speaking units.

Cobbe finished his letter by invoking the Queen’s patronage of the Regiment.

'Her Majesty has called the 2nd Battalion by her own maiden name and has on 3 successive occasions presented it with Colours. On 3rd August next the 66th Anniversary of the first presentation will occur. I therefore sincerely trust that His Lordship the Field Marshal Commander-in-Chief will be pleased to submit this application for the Queen’s most gracious approval, in order to commemorate in this most popular and national way the very long interest which Her Majesty has taken in her Irish Fusiliers.'

The most determined opponent of Cobbe’s application was the Adjutant General. Wood was scathing in his comments. He wrote to the Commander-in-Chief on 18 September 1899:

'This demand for a distinction to an Irish regiment was refused in 1890 and in 1893. I cannot see that there is any reason for putting ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’ [amended in manuscript to ‘Fag an beaulach’] on to the Colours of a regiment because it is stated that one battalion of that regiment shouted ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’ as they charged at Barrosa. The regiment bears Barrosa on its Colours, apparently because it there distinguished itself. I assume that if Lord Wellington had thought its services entitled to the motto, the regiment would have had it before now.

'I believe the battalion now does not shout ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’ when it is pleased but ‘Oooh’ [amended in manuscript to ‘Hooh’; presumably this was ‘Yoh’, more commonly associated with the Connaught Rangers]. I apprehend that if this motto were given it would be difficult to resist other claims such as the ‘Die hards’, which indeed appeals more to an Adjutant General than ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’, inasmuch as the encomium is derived from a superior officer having thus encouraged the men to fight.

'I think this application should be refused because it is neither ‘an ancient badge, nor a device, nor a distinction, nor a motto given in the Army List’ (appendix XI, para 10, Clothing Regulations).'

The reply tells us much about Wood’s attitude to the ‘common soldier’ and, perhaps, his attitude to Irish soldiers. One suspects he was unprepared for the response of the Commander-in-Chief who wrote on the file, in his own hand:

'I see no good reason why this Regt should not have on their drums and Colours a motto used in action by its Colonel – Lord Gough – at the memorable battle of Barrossa [sic] where it took a French Eagle. It is in my opinion a motto more apt … than many which are in Latin & borne on the Colours of certain Regts at this moment. The Regt has a good history & I recommend that it may be allowed this well earned distinction.'

The Commander-in-Chief was none other than Field Marshal Sir Garnet Wolseley, born and educated in Dublin, and Colonel of the Royal Irish Regiment. Was Wolseley so offended by Wood’s comments that he supported the Faughs’ claim without question? In any event the proposal then went to the ‘ministry’ men where support was expressed in the words ‘If the 25th can write upon its colours ‘Nisi Dominus frustra’ or ‘Nec Aspera Terrent’ I would not deny the R. Ir. F. the privilege of inscribing theirs with this time honoured legend.'

Wolseley then replied to Wood on 26 September with the curt command ‘Carry out. W.’.

Interestingly, though, on 29 September, someone added, again in manuscript, the comment ‘The correct Irish is ‘Fag an beaulach’.’ In fact, the correct Irish is Fág an Bealach – there is no ‘u’ in the last word. (It was also pointed out that this means ‘Get off the Road’.) Here began another discussion – on the exact words to be placed on the Colours. Should they be ‘Faugh–a–Ballagh’, as traditionally used in the Regiment, an anglicised version of the old Gaelic war cry, or the correct Irish ‘Fág an Bealach’? Expert opinion was sought (and this from someone who wrote ‘I was in Scotland’) with the Regiment willing to accept either version.

Finally, in December 1899 the wording to appear in the official order approving the proposal was submitted to the Secretary of State before going to the Queen:

Honorary Distinction – The Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers). – Her Majesty the Queen has been graciously pleased to approve of the Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) being permitted to adopt and inscribe on its colours the motto – ‘FAUGH–À–BALLAGH’

This wording of the motto included an accent over the ‘a’ which is not to be found in Irish Gaelic, although it is in Scots Gaelic. But, as so much had already been changed from the original, did it make any real difference? Probably not and that errant Scottish accent has long since been forgotten.

There is a sad ending to this story. It began with General Cobbe’s letter to the War Office seeking approval for a green hackle and the inscribing of the Regimental motto on the Colours. By the time approval had been gained, General Cobbe had died. In fact, he expired on 13 September 1899, before even the green hackle had been approved. He was succeeded as Colonel of the Regiment by Major General T. R. Stevenson CB, who had continued with Cobbe’s campaign.

The information in this article is from WO32/3260 in the National Archives. Both unsuccessful requests to have the motto placed on the Colours were made when the Duke of Cambridge, who was notoriously reactionary, was Commander-in-Chief. General Cobbe’s son, Alexander, earned the Victoria Cross in Somaliland in October 1902 and later became a lieutenant general in the Indian Army. The Cobbe family came from Newbridge, County Kildare.